This post originally appeared on student Theo Acker’s website.

Digital accessibility, ensuring that digital content is accessible to people with disabilities, is a topic near and dear to my heart. The truth of the matter is that I kind of stumbled into learning about it, and only then realized just how little I know and how inaccessible so much web content is. This is something we need to be talking about.

Importance of Digital Accessibility

The Feminist Data Manifest-No has two points that reference digital accessibility. Statement seventeen calls out Big Tech’s way of deferring the needs of vulnerable users to be dealt with later, while statement eighteen goes on to explicitly discuss accessible design and how it is delayed “because it is too expensive, inconvenient, or not legally required.” Often, it seems that accessibility becomes an afterthought that may be put off indefinitely, when in reality web content should be designed and created with accessibility in mind throughout the entire process.

But why is it so important for digital cultural heritage content to be accessible to people with disabilities? Beyond the obvious that they should have access to the digital cultural record just like anyone else, they certainly have a right to know how they are represented within it. For example, projects representing people of color are also representing people of color with disabilities. Is this subset excluded from knowing how their heritage is represented, or from objecting to wrongful use of it?

This idea extends to the discussion about digital public squares from Unit F. Roued-Cunliffe (2017) discusses Wikipedia and the relatively unvaried demographics of its editors. Ultimately, the editors are deciding how history and heritage will be represented to a sizable percentage of the population. People with disabilities need to be able to use tools like Wikipedia effectively enough to edit content, or else they risk not being represented or being represented poorly.

Universal Design

A theme that has come up several times in this course is that people in different cultures may have radically different ways of thinking or knowing. What might seem like a universal value might actually be diametrically opposed to the values of some groups. Risam (2018) writes about the importance of realizing that “universal” ideas tend to come from the Global North and may not truly be universal.

Digital accessibility, as Williams (2012) points out, is another way of recognizing that “normal” just refers to standards imposed by a dominant group. There are many ways to interact with digital content, and “tools that assume everyone approaches information with the same abilities and using the same methods risk excluding a large percentage of people. In fact, such tools actually do the work of disabling people by preventing them from using digital resources altogether” (para 2). Embracing digital accessibility, then, means thinking beyond the one way we would prefer to view or work with our own content and considering how others might need or want to access it. Universal design is about allowing for multiple ways of interacting with content so that as many people as possible can access it.

The State of Digital Accessibility

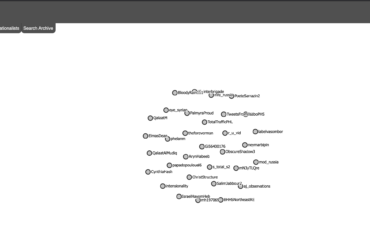

Unfortunately, digital accessibility often goes neglected (Williams, 2012). I ran a simple automated tool called WAVE on the first page of several of the projects we’ve looked at this semester, to disappointing results. Automated tests generally catch fewer than 50% of potential errors, but they are recommended as one part of the testing process. As an example, here is an image of the WAVE results for the Livingstone Online project, which was on the lower (better) end of number of errors I found. Red symbols indicate errors. Orange symbols indicate alerts – these tend to be things that might or might not be issues depending on a variety of factors. WAVE makes note of a few other elements, but these can be ignored, so I turned them off before taking the screenshot.

In my own work I have been struggling with accessibility and tools like WordPress and Omeka. WordPress has a lot of material regarding accessibility, but there is a lot to wade through. Not every theme labeled “accessibility ready” is truly accessible. Omeka has a much smaller user-base, so not as much accessibility work has been done.

The problem is that for most researchers and content creators, designing a website from scratch is out of the question (or at least, designing a good one) due to time, expense, and required expertise. Thus, they must rely on pre-made content management systems, which therefore limits what they can do. With luck, anything inaccessible can either be avoided (by not using a given feature) or fixed with a limited amount of coding. Digital accessibility doesn’t mean that websites have to be boring – all kinds of fancy content can be made accessible, but someone relying on pre-made content may find themselves limited by the available options.

There is much to learn and do, but ultimately it is time for museums, libraries, and other cultural heritage institutions to take a stand with the Feminist Data Manifest-No and refuse to put off working on digital accessibility until some nebulous future date.

References

Cifor, M., Garcia, P., Cowan, T.L., Rault, J., Sutherland, T., Chan, A., Rode, J., Hoffmann, A.L., Salehi, N., & Nakamura, L. (2019). Feminist Data Manifest-No. Retrieved from: https://www.manifestno.com/

Risam, R. (2018). New digital worlds: Postcolonial digital humanities in theory, praxis, and pedagogy. Northwestern University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7tq4hg

Roued-Cunliffe, H. (2017). Forgotten history on Wikipedia. In H. Roued-Cunliffe & A. Copeland (Eds.), Participatory heritage (pp. 67-76). Facet. https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301256.008

Williams, G. H. (2012). Disability, universal design, and the digital humanities. In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the digital humanities (ch. 12). University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452963754